mardi, 24 avril 2012

Mesianismo tecnológico. Ilusiones y desencanto.

|

|

|

|

Por Horacio Cagni* Ex: http://disenso.org Las contradicciones del progreso, y particularmente la tremenda experiencia de las guerras del S. XX, pusieron sobre el tapete los alcances de la ciencia y la técnica, obligando a pensadores de todo origen y procedencia a interrogarse angustiosamente sobre el destino de nuestra civilización. Al analizar aspectos emblemáticos como los gulags soviéticos, el genocidio armenio por los otomanos, o el Holocausto –el exterminio de judíos por el nazismo en la Segunda Guerra Mundial– así como las consecuencias del eufemísticamente llamado bombardeo estratégico angloamericano –que, tanto en dicho conflicto como en otros posteriores, era simple terrorismo aéreo–, se puede concluir que estas masacres en serie son consecuencia de la planificación y organización propias de las industrias de gran escala. La muerte industrial, la objetivación de un grupo social o de un colectivo a destruir, resulta obvio para los estudiosos del Holocausto y del aniquilamiento racial, como para aquellos que se dedicaron a la revisión del aniquilamiento social que realizaron los comunistas con burgueses, reaccionarios o “desviacionistas”. En dichos casos, la presencia del confinamiento en campos de concentración y de exterminio, los lager y los gulags , resultan imágenes por demás familiares. Menos asiduas son aquellas que corresponden a la destrucción de ciudades y la muerte masiva de población civil, aduciendo tácticas y estrategias de ataque de industrias y centros neurálgicos económicos, administrativos y políticos del enemigo. Si bien nadie duda de la indefensión de los concentrados en los campos de exterminio, sean armenios, judíos o kulacs , resulta cada vez más difícil sostener que las poblaciones de Alemania, Japón, Vietnam, Serbia, Afganistán o Irak sean considerados objetivos militares válidos. En todos los casos, la distancia que la tecnología pone entre victimarios y víctima asegura la despersonalización de esta última, convertida en simple material a exterminar; los que están hacinados esperando el fin en un campo de concentración ante el administrador de su muerte, como los trasegados civiles que están bajo la mira del bombardero, no son más que simples números sin rostro. La responsabilidad del genocidio se diluye en la inmensa estructura tecnoburocrática, lo que Hanna Arendt llamaba “la banalidad del mal”. Es útil recordar que, a lo largo de todo el siglo pasado, numerosas voces se alzaron, lúcidamente, para denunciar los límites de la técnica y los peligros del mesianismo tecnológico. La técnica, clave de la modernidad, se constituyó en una religión del progreso, y la máquina resultó igualmente venerada y ensalzada por liberales, comunistas, nazifascistas, reaccionarios y progresistas. Guerra y técnica. La crítica de Ernst Jünger Escritor, naturalista, soldado, muerto más que centenario poco antes del 2000, Ernst Jünger ha sido el testigo lúcido y el crítico agudo de una de las épocas más intensas y cataclísmicas de la historia, de ese siglo tan breve, que Eric Hobsbawm sitúa entre el fin de la belle époque en 1914, y la caída del Muro de Berlín y de la utopía comunista, en 1991. Nunca se insistirá lo suficiente que, para entender a Jünger y las corrientes espirituales de su tiempo, que también es el nuestro, la clave, una vez más, es la Gran Guerra. El primer conflicto mundial fue la gran partera de las revoluciones de este siglo, no sólo en el plano ideológico y político sino en el de las ideas, la ciencia y la técnica. Por primera vez todas las instancias de la vida humana se subsumían y subordinaban al aspecto bélico. Era la consecuencia lógica de la Revolución Industrial, el orgullo de Europa, pero además necesitó de la conjunción con un nuevo fenómeno sociopolítico, que George Mosse definiera con acierto “la nacionalización de las masas”. En todos los países beligerantes, pero sobre todo en Italia y Alemania, culminaba el proceso de coagulación nacional y de exaltación de la comunidad. Países que habían advenido tarde, merced a las vicisitudes históricas, al logro de una unidad interior –como los señalados–, habían encontrado finalmente esa unidad en el frente. En las trincheras se dejaba de lado los dialectos, para mandar y obedecer en la lengua nacional; en el barro y bajo el alud de fuego se vivía y se moría de forma absolutamente igualitaria. Abrumados ante tamaño desastre, esos hombres “civilizados” se encontraron con que su única arma y esperanza era la voluntad, y su único mundo los camaradas del frente. Atrás habían quedado los orgullosos ideales de la Ilustración. El juego de la vida en buenas formas y la retórica folletinesca-parisina quedaban enterrados en el lodo de Verdún y de Galizia, en las rocas del Carso y las frías aguas del Mar del Norte. La catástrofe no sólo significó el hundimiento del positivismo sino que demostró hasta qué punto había avanzado la técnica en su desmesurado desarrollo, y hasta qué grado el ser humano estaba sometido a ella. Soldados y máquinas de guerra eran una misma cosa, juntamente con sus Estados Mayores y la cadena de producción bélica. Ya no existía frente y retaguardia, pues la movilización total se había apoderado del alma del pueblo. Jünger, oficial del ejército del Káiser, llamó Mate - rialschlacht –batalla de material– a esta novedosa especie de combate. En las operaciones bélicas, todo devenía material, incluso el individuo, quien no podía escapar de la operación conjunta de hombres y máquinas que nunca llegaba a entender. Cuando se leen las obras de Jünger sobre la Gran Guerra –editadas por Tusquets–, como Tempestades de Acero o El bosquecillo 125, el relato de las acciones bélicas se vuelve monótono y abrumador, como debe haber sido la vida cotidiana en el frente, suspendida en el riesgo, que insensibiliza a fuerza de mortificación. En La guerra como experiencia interna, Jünger acepta la guerra como un hecho inevitable de la existencia, pues existe en todas las facetas del quehacer humano: la humanidad nunca hizo otra cosa que combatir. La única diferencia estriba en la presencia omnímoda y despersonalizante de la técnica, pero siempre somos más fuertes o más débiles. La literatura creada por la Gran Guerra es numerosa, y a veces magnífica. A partir de El Fuego de Henri Barbusse, que fue la primera, una serie de obras contaron el dolor y el sacrificio, como la satírica El Lodo de Flandes, de Max Deauville, Guerra y Postguerra de Ludwig Renn, Camino del Sacrificio de Fritz von Unruh, y las reconocidas Sin Novedad en el Frente, de Erich Remarque y Cuatro de Infantería, de Ernst Johannsen, que dieron lugar a sendos filmes. En todas estas obras –traducidas al español en su momento y editadas por Claridad– campea la sensación de impotencia del hombre frente a la técnica desencadenada. Pero, más allá de su excelencia literaria, todas se agotan en la crítica de la guerra y el sentido deseo de que nunca vuelva a repetirse la tragedia. Jünger fue mucho más lejos; comprendió que este conflicto había destruido las barreras burguesas que enseñaban la existencia como búsqueda del éxito material y observación de la moral social. A h o r a afloraban las fuerzas más profundas de la vida y la realidad, lo que él denominaba “elementales”, fuerzas que a través de la movilización total se convertían en parte activa de la nueva sociedad, formada por hombres duros y jóvenes, una generación abismalmente diferente de la anterior. El nuevo hombre se basaba en un “ideal nuevo”; su estilo era la totalidad y su libertad la de subsumirse, de acuerdo a la categoría de la función, en una comunidad en la cual mandar y obedecer, trabajar y combatir. El individuo se subsume y tiene sentido en un Estado total. Individuo y totalidad se conjugan sin trauma alguno merced a la técnica, y su arquetipo será el trabajador, símbolo donde el elemental vive y, a la vez, es fuerza movilizadora. Si bien el ejemplo es el obrero industrial, todos son trabajadores por encima de diferencias de clase. El tipo humano es el trabajador, sea ingeniero, capataz, obrero, ya se encuentre en la fábrica, la oficina, el café o el estadio. Opuesto al “hombre económico” –alma del capitalismo y del marxismo por igual–, surgía el “hombre heroico”, permanentemente movilizado, ya en la producción, ya en la guerra. Esta distinción entre hombre económico y hombre heroico la había esbozado tempranamente el joven Peter Drucker en su libro The end of the economic man, d e 1939, haciendo alusión al fascismo y al nacionalsocialismo, que irrumpían en la historia de la mano de “artistas de la política”, que habían vislumbrado la misión redentora y salvífica de unidad nacional en las trincheras donde habían combatido. El trabajador es “persona absoluta”, con una misión propia. Consecuencia de la era tecnomaquinista, es pertenencia e identidad con el trabajo y la comunidad orgánica a la cual pertenece y sirve, señala Jünger en su libro Der Arbeiter, uno de sus mayores ensayos, escrito en 1931. Lo más importante de esta obra es la consideración del trabajador como superación de la burguesía y del marxismo: Marx entendió parcialmente al trabajador, pues el trabajo no se somete a la economía. Si Marx creía que el trabajador debía convertirse en artista, Jünger sostiene que el artista se metamorfosea en trabajador, pues toda voluntad de poder se expresa en el trabajo, cuya figura es dicho trabajador. En cuanto al meollo del pensamiento burgués, éste reniega de toda desmesura, intentando explicar todo fenómeno de la realidad desde un punto de vista lógico y racional. Este culto racionalista desprecia lo elemental como irracional, terminando por pretender un vaciamiento de sentido de la existencia misma, erigiendo una religión del progreso, donde el objetivo es consumir, asegurándose una sociedad pacífica y sin sobresaltos. Para Jünger esto conduce al más venenoso y angustiante aburrimiento existencial, un estado espiritual de asfixia y muerte progresiva. Sólo un “corazón aventurado”, capaz de dominar la técnica asumiéndola plenamente y dándole un sentido heroico, puede tomar la vida por asalto y, de este modo, asegurar al ser humano no simplemente existir sino ser realmente . Otros críticos del tecnomaquinismo A principios de los años treinta, aparecieron en Europa, sobre todo en Alemania, una serie de escritores cuyas obras se referían a la relación del hombre con la técnica, donde la voluntad como eje de la vida resulta una constante. Así ocurre en El Hombre y la Técnica, de Oswald Spengler (Austral) –quien sigue las premisas nietzscheanas de la “voluntad de poder”–, La filosofía de la Técnica de Hans Freyer, Perfección y fracaso de la técnica de Friedrich Georg Jünger –hermano de Ernst– y los seminarios del filósofo Martín Heidegger, todos contemporáneos del mencionado El Trabajador. (El libro de su hermano Friedrich fue editado inmediatamente después de la 2° Guerra, pero había sido escrito muchos años antes y por las vicisitudes del conflicto no había podido salir a luz; existe versión castellana de Sur). Pero estos interrogantes no eran privativos del mundo germánico, pues no debemos olvidar a los futuristas italianos liderados por Filippo Marinetti, ni al Luigi Pirandello de Manivelas, a los escritos del francés Pierrre Drieu La Rochelle –como La Comédie de Charleroi– y a la película Tiempos Modernos, de Charles Chaplin. El autor de El Principito, el notable escritor y aviador francés Antoine de Saint Exupéry, también hace diversas reflexiones sobre la técnica. En su libro Piloto de Guerra (Emecé) hay una página significativa, cuando señala que, en plena batalla de Francia en 1940, en una granja solariega, un anciano árbol “bajo cuya sombra se sucedieron amores, romances y tertulias de generaciones sucesivas” obstaculiza el campo de tiro “de un teniente artillero alemán de veintiséis años”, quien termina por suprimirlo. Reacio a emplear su avión como máquina asesina, St. Ex, como le llamaban, desapareció en vuelo de reconocimiento en 1944, sin que se hayan encontrado sus restos. Su última carta decía: “si regreso ¿qué le puedo decir a los hombres?” También el destacado jurista y politólogo Carl Schmitt se planteó la cuestión de la técnica. Tempranamente, en su clásico ensayo El concepto de lo político –de múltiples ediciones–, afirma que la técnica no esuna fuerza para neutralizar conflictos sino un aspecto imprescindible de la guerra y del dominio. “La difusión de la técnica –señala– es indetenible”, y “el espíritu del tecnicismo es quizás maligno y diabólico, pero no para ser quitado de en medio como mecanicista, es la fe en el poder y el dominio ilimitado del hombre sobre la naturaleza”. La realidad, precisamente, demostraba los efectos del mesianismo tecnológico, tanto en la explotación de la naturaleza, como en el conflicto entre los hombres. En un corolario a la obra antedicha, Schmitt define como p roceso de neutralización de la cultura a esta suerte de religión del tecnicismo, capaz de creer que, gracias a la técnica, se conseguirá la neutralidad absoluta, la tan deseada paz universal. “Pero la técnica es ciega en términos culturales, sirve por igual a la libertad y al despotismo... puede aumentar la paz o la guerra, está dispuesta a ambas cosas en igual medida”. Lo que ocurre, según Schmitt, es que la nueva situación creada por la Gran Guerra ha dejado paso a un culto de la acción viril y la voluntad absolutamente contraria al romanticismo del ochocientos, que había creado, con su apoliticismo y pasividad, un parlamentarismo deliberativo y retórico, arquetipo de una sociedad carente de formas estéticas. Es innegable la influencia de los escritos de posguerra de Jünger –la guerra forjadora de una “estética del horror”– en la enjundiosa mente de Schmitt. Pero a esa desesperada búsqueda de una comunidad de voluntad y belleza, capaz de conjurar al Golem tecnológico mediante una barbarie heroica, no escapaba prácticamente nadie en aquellos tiempos. Hoy es fácil mirar hacia atrás y señalar a tantos pensadores de calidad como “enterradores de la democracia de Weimar” y “preparadores del camino del nazismo”. Esta mirada superficial sobre un período histórico tan intenso y complejo se impuso al calor de las pasiones, apenas terminada la Segunda Guerra Mundial y, luego, más aún desde que el periodismo se apoderó progresivamente de la historia y la ciencia política. La realidad es siempre más profunda. En aquellos años de Weimar, los alemanes en su mayoría sentían la frustración de 1918 y las consecuencias de Versalles; los jóvenes buscaban con ahínco encarnar una generación distinta, edificar una sociedad nueva que reconstruyera la patria que amaban con desesperación. Fue una época de increíble florecimiento en la literatura, las artes y las ciencias, y obviamente, esto se trasladó al campo político. Por entonces, Moeller van der Bruck, Spengler y Jünger –malgrado sus diferencias– se transformaron en educadores de esa juventud, a través de escritos y conferencias. La estética völkisch, popular, que era anterior al nacionalsocialismo, teñía todos los aspectos de la vida cotidiana. La mayoría de los pensadores abjuraban del débil parlamentarismo de la República surgida de la derrota, y en el corazón del pueblo, la Constitución de Weimar estaba condenada. ¿Acaso no había sido un éxito editorial El estilo prusiano, de Moeller van der Bruck, que proponía una educación por la belleza? ¿Y Heidegger? En su alocución del solsticio de 1933 dirá: “los días declinan/nuestro ánimo crece/llama, brilla/corazones, enciéndanse” Lo interesante es que todos coincidían. El católico Schmitt, cuando en su análisis Caída del Segundo Imperio sostenía que la principal razón estribaba en la victoria del burgués sobre el soldado; neoconservadores como August Winning, que distinguía entre comunidad de trabajo y proletariado, y como Spengler con su “prusianismo socialista”; el erudito Werner Sombart y su oposición entre “héroes y mercaderes”, y, además, los denominados nacionalbolcheviques. El más conspicuo de los intelectuales nacionalbolcheviques, Ernst Niekisch, había conocido a Jünger en 1927; a partir de allí elaborará también una reflexión sobre la técnica. Su breve ensayo La técnica, devoradora de hombre s es uno de los análisis más lúcidos del mesianismo tecnológico, y una de las mayores críticas de la incapacidad del marxismo para comprender que la técnica era una cuestión que escapaba al determinismo economicista y a las diferencias de clase. También es de Niekisch uno de los mejores comentarios de El Trabajador de Jünger, obra de la cual tenía un gran concepto. Todos ellos intentaron dotar a la técnica de un rostro brutal, pero aún humano, demasiado humano, único hallazgo del mundo, como sostuvo Nietzsche. Por supuesto, todas estas energías fueron aprovechadas por los políticos, que no pensaban ni escribían tanto, pero podían franquear las barreras que los intelectuales no se atrevían a traspasar. Estos nuevos políticos poseían esa nueva filosofía: ya no procedían de cuadros ni eran profesionales de la política sino “artistas del poder”, como decía Drucker. Lenin abrió el camino, pero hombres como Mussolini y Hitler, y muchos de sus secuaces, eran arquetipos de esta nueva clase. Provenían de las trincheras del frente, eran conductores de un movimiento de jóvenes, tenían una gran ambición, despreciaban al burgués, si bien confundían sus ideas de salvación nacional con el lastre ochocentista de diversos prejuicios. El fin de una ilusión Schmitt coincidía con Jünger en su desprecio del mundo burgués. En la concepción jüngeriana, tan importante era el amigo como el enemigo: ambos son referentes de la propia existencia y le otorgan sentido. El postulado significativo de la teorética schmittiana será la específica distinción de lo político: la distinción entre amigo y enemigo. El concepto de enemigo no es aquí metafórico sino existencial y concreto, pues el único enemigo es el enemigo público, el hostis. Preocupado de la ausencia de unidad interior de su país luego de la debacle de 1918, vislumbrando en política interior el costo de la debilidad del Estado liberal burgués, y en política exterior las falencias del sistema internacional de posguerra, Schmitt, al principio, se comprometió profundamente con el nacionalsocialismo. Llegó a ser uno de los principales juristas del régimen. Creía encontrar en él la posibilidad de realización del decisionismo, la encarnación de una acción política independiente de postulados normativos. Jünger, atento a lo que denominaba “la segunda conciencia más lúcida y fría” –la posibilidad de verse a sí mismo actuando en situaciones específicas– fue más cuidadoso, y se distanció progresivamente de los nacionalsocialistas. Sin duda, su costado conservador había vislumbrado los excesos del plebeyismo nazifascista y su fuerza niveladora. También Schmitt comenzó a ver cómo elementos mediocres e indeseables se entroncaban en el régimen y adquirían cada vez más poder. Heidegger, al principio tan entusiasta, se había alejado del régimen al poco tiempo. Spengler murió en 1936, pero los había criticado desde el inicio. No obstante, había diferencias de fondo. Spengler, Schmitt y Jünger creían que un Estado fuerte necesitaba de una técnica poderosa, pues el primado de la política podía reconciliar técnica y sociedad, soldando el antagonismo creado por las lacras de la revolución industrial y tecnomaquinista. Eran antimarxistas, antiliberales y antiburgueses, pero no antitecnológicos, como sí lo era Heidegger; éste se había retirado al bosque a rumiar su reflexión sobre la técnica como obstáculo al “desocultamiento del ser”, que tan magistralmente explicitara mucho después. Otro aspecto en el cual coincidían Jünger, Schmitt, y también Niekisch, era en su consideración cómo la Rusia stalinista se alineaba con la tendencia tecnológica imperante en el mundo. Al finalizar los treinta, dos naciones aparentaban sobresalir como ejemplo de una voluntad de poder orientada y subsumida en una comunidad de trabajadores, malogrado sus principios y sistemas políticos diferentes: el III Reich y la URSS stalinista (en menor medida también la Italia fascista). Pero, obviamente, sus clases dirigentes no eran permeables a las consideraciones jüngerianas o schmittianas, pues la carcaza ideológica no podía admitir actitudes críticas. AJünger y a Schmitt les ocurrió lo mismo: no fueron considerados suficientemente nacionalsocialistas y comenzaron a ser criticados y atacados. Schmitt se refugió en la teorización –brillante, sin duda– sobre política internacional. En cuanto a Jünger, su concepción del “trabajador” fue rechazada por los marxistas, acusándola de cortina de humo para tapar la irreductible oposición entre burguesía y proletariado –es decir “fascista”– tanto como por los nazis, quienes no encontraban en ella ni rastros de problemática racial. En su exilio interior, Jünger escribió una de sus novelas más importantes. Los acantilados de mármol; constituye una reflexión profunda, enclave simbólica, sobre la concentración del poder y el mundo de sencadenado de los “elementales”. Mediante una prosa hiperbólica y metafórica, denuncia la falacia de la unión de principios guerreros e idealistas cuando falta una metafísica de base. Por supuesto que esta obra, editada en vísperas de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, fue considerada, no sin razón, una crítica del totalitarismo hitleriano, pero no se agota allí. El escritor va más lejos, pues se refiere al mundo moderno donde ninguna revolución, por más restauradora que se precise, puede evitar la caída del hombre y sus dones de tradición, sabiduría y grandeza. Jünger siempre ha sido un escéptico. En La Movilización Total hay un párrafo esclarecedor: “Sin discontinuidad, la abstracción y la crudeza se acentúan en todas las relaciones humanas. El fascismo, el comunismo, el americanismo, el sionismo, los movimientos de emancipación de pueblos de color, son todos saltos en pos del progreso, hasta ayer impensables. El progreso se desnaturaliza para proseguir su propio movimiento elemental, en una espiral hecha de una dialéctica artificial”. Contemporáneamente, Schmitt señalaba: “Bajo la inmensa sugestión de inventos y realizaciones, siempre nuevos y sorprendentes, nace una religión del progreso técnico, que resuelve todos los problemas. La religión de la fe en los milagros se convierte enseguida en religión de los milagros técnicos. Así se presenta el S. XX, como siglo no sólo de la técnica sino de la creencia religiosa en ella”. Si ambos pensadores creían en un intento de ruptura del ciclo cósmico desencadenado, rápidamente habrán perdido sus esperanzas. Los propios desafiantes del fenómeno mundial de homogeneización –cuyo motor era la técnica originada en el mundo anglosajón de la revolución industrial–, como el nacionalsocialismo y el sovietismo, mal podían llevar adelante este proceso de ruptura cuando constituían parte importante, y en muchos casos la vanguardia, del progreso tecnológico. No hay escapatoria posible para el hombre actual y el principio totalitario, frío, cínico e inevitable que Jünger vislumbró desde sus primeras obras, y que siguió desarrollando hasta su final, será la característica esencial de la sociedad mundialista. El desenlace de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, con su horror desencadenado, liquidó la posibilidad de entronización del tan mentado “hombre heroico” y consagró el “hombre económico” o “consumista” como arquetipo. Este evidente triunfo de la sociedad fukuyamiana se debió no sólo a la prodigiosa expansión de la economía sino esencialmente, al auge tecnológico y a la democratización de la técnica. Ello no implica, no obstante, que el hombre sea más libre; se cree libre en tanto participa de democracias cuatrimestrales, habitante del shopping y esclavo del televisor y de la computadora, productor y consumidor en una sociedad que ha obrado el milagro de crear el ansia de lo innecesario, la aparente calma en la que vive esconde aspectos ominosos. La tecnología ha despersonalizado totalmente al ser humano, lo cual se evidencia en la macroeconomía virtual, que esconde una espantosa explotación, desigualdad y miseria, así como en las guerras humanitarias,eufemismo que subsume la tragedia de las guerras interétnicas y seudorreligiosas, vestimenta de la desembozada explotación de los recursos naturales por parte de los poderes mundiales. Desde el FMI hasta la invasión de Irak, el “filisteo moderno del progreso” –Spengler dixit– es, bajo sus múltiples manifestaciones, genio y figura. En sus últimos tiempos, Jünger estaba harto. Su consejo para el rebelde era hurtarse a la civilización, la urbe y la técnica, refugiándose en la naturaleza. El actual silencio de los jóvenes –sostenía en La Emboscadura , mejor traducida como Tratado del Rebelde– es más significativo aún que el arte. Al derrumbe del Estado-Nación le ha seguido “la presencia de la nada a secas y sin afeites. Pero de este silencio pueden s u rgir nuevas formas”. Siempre el hombre querrá ser diferente, querrá algo distinto. Y, como la calma que precede a la tormenta, todo estado de quietud y todo silencio es engañoso. * Politólogo especializado en Relaciones Internacionales. Ensayista. |

|

|

|

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, révolution conservatrice, ernst jünger, allemagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 17 avril 2012

Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing, RIP

PAUL GOTTFRIED is the Raffensperger Professor of Humanities at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania.

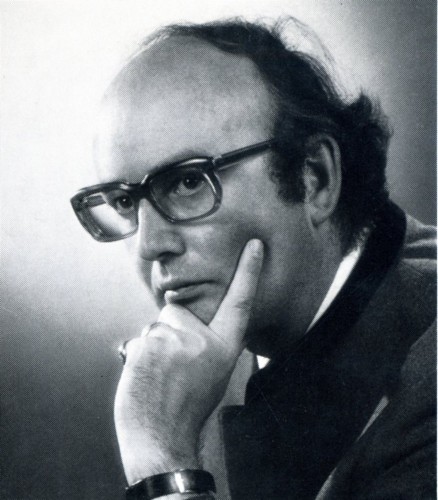

The death of Caspar von Schrenck- Notzing on January 25, 2009, brought an end to the career of one of the most insightful German political thinkers of his generation. Although perhaps not as well known as other figures associated with the postwar intellectual Right, Schrenck- Notzing displayed a critical honesty, combined with an elegant prose style, which made him stand out among his contemporaries. A descendant of Bavarian Protestant nobility who had been knights of the Holy Roman Empire, Freiherr von Schrenck- Notzing was preceded by an illustrious grandfather, Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, who had been a close friend of the author Thomas Mann. While that grandfather became famous as an exponent of parapsychology, and the other grandfather, Ludwig Ganghofer, as a novelist, Caspar turned his inherited flair for language toward political analysis.

Perhaps he will best be remembered as the editor of the journal Criticón, which he founded in 1970, and which was destined to become the most widely read and respected theoretical organ of the German Right in the 1970s and 1980s. In the pages of Criticón an entire generation of non-leftist German intellectuals found an outlet for their ideas; and such academic figures as Robert Spämann, Günter Rohrmöser, and Odo Marquard became public voices beyond the closed world of philosophical theory. In his signature editorials, Criticón's editor raked over the coals the center-conservative coalition of the Christian Democratic (CDU) and the Christian Social (CSU) parties, which for long periods formed the postwar governments of West Germany.

Despite the CDU/CSU promise of a "turn toward the traditional Right," the hoped-for "Wende nach rechts" never seemed to occur, and Helmut Kohl's ascent to power in the 1980s convinced Schrenck- Notzing that not much good could come from the party governments of the Federal Republic for those with his own political leanings. In 1998 the aging theorist gave up the editorship of Criticón, and he handed over the helm of the publication to advocates of a market economy. Although Schrenck-Notzing did not entirely oppose this new direction, as a German traditionalist he was certainly less hostile to the state as an institution than were Criticón's new editors.

But clearly, during the last ten years of his life, Schrenck-Notzing had lost a sense of urgency about the need for a magazine stressing current events. He decided to devote his remaining energy to a more theoretical task—that of understanding the defective nature of postwar German conservatism. The title of an anthology to which he contributed his own study and also edited, Die kupierte Alternative (The Truncated Alternative), indicated where Schrenck-Notzing saw the deficiencies of the postwar German Right. As a younger German conservative historian, Karl- Heinz Weissmann, echoing Schrenck- Notzing, has observed, one cannot create a sustainable and authentic Right on the basis of "democratic values." One needs a living past to do so. An encyclopedia of conservatism edited by Schrenck-Notzing that appeared in 1996 provides portraits of German statesmen and thinkers whom the editor clearly admired. Needless to say, not even one of those subjects was alive at the time of the encyclopedia's publication.

What allows a significant force against the Left to become effective, according to Schrenck-Notzing, is the continuity of nations and inherited social authorities. In the German case, devotion to a Basic Law promulgated in 1947 and really imposed on a defeated and demoralized country by its conquerors could not replace historical structures and national cohesion. Although Schrenck-Notzing published opinions in his journal that were more enthusiastic than his own about the reconstructed Germany of the postwar years, he never shared such "constitutional patriotism." He never deviated from his understanding of why the post-war German Right had become an increasingly empty opposition to the German Left: it had arisen in a confused and humiliated society, and it drew its strength from the values that its occupiers had given it and from its prolonged submission to American political interests. Schrenck-Notzing continually called attention to the need for respect for one's own nation as the necessary basis for a viable traditionalism. Long before it was evident to most, he predicted that the worship of the postwar German Basic Law and its "democratic" values would not only fail to produce a "conservative" philosophy in Germany; he also fully grasped that this orientation would be a mere transition to an anti-national, leftist political culture. What happened to Germany after 1968 was for him already implicit in the "constitutional patriotism" that treated German history as an unrelieved horror up until the moment of the Allied occupation.

For many years Schrenck-Notzing had published books highlighting the special problems of post-war German society and its inability to configure a Right that could contain these problems. In 2000 he added to his already daunting publishing tasks the creation and maintenance of an institute, the Förderstiftung Konservative Bildung und Forschung, which was established to examine theoretical conservative themes. With his able assistant Dr. Harald Bergbauer and the promotional work of the chairman of the institute's board, Dieter Stein, who also edits the German weekly, Junge Freiheit, Schrenck-Notzing applied himself to studies that neither here nor in Germany have elicited much support. As Schrenck-Notzing pointed out, the study of the opposite of whatever the Left mutates into is never particularly profitable, because those whom he called "the future-makers" are invariably in seats of power. And nowhere was this truer than in Germany, whose postwar government was imposed precisely to dismantle the traditional Right, understood as the "source" of Nazism and "Prussianism." The Allies not only demonized the Third Reich, according to Schrenck-Notzing, but went out of their way, until the onset of the Cold War, to marginalize anything in German history and culture that was not associated with the Left, if not with outright communism.

This was the theme of Schrenck-Notzing's most famous book, Charakterwäsche: Die Politik der amerikanischen Umerziehung in Deutschland, a study of the intent and effects of American re-education policies during the occupation of Germany. This provocative book appeared in three separate editions. While the first edition, in 1965, was widely reviewed and critically acclaimed, by the time the third edition was released by Leopold Stocker Verlag in 2004, its author seemed to be tilting at windmills. Everything he castigated in his book had come to pass in the current German society—and in such a repressive, anti-German form that it is doubtful that the author thirty years earlier would have been able to conceive of his worst nightmares coming to life to such a degree. In his book, Schrenck-Notzing documents the mixture of spiteful vengeance and leftist utopianism that had shaped the Allies' forced re-education of the Germans, and he makes it clear that the only things that slowed down this experiment were the victories of the anticommunist Republicans in U.S. elections and the necessities of the Cold War. Neither development had been foreseen when the plan was put into operation immediately after the war.

Charakterwäsche documents the degree to which social psychologists and "antifascist" social engineers were given a free hand in reconstructing postwar German "political culture." Although the first edition was published before the anti-national and anti-anticommunist German Left had taken full power, the book shows the likelihood that such elements would soon rise to political power, seeing that they had already ensconced themselves in the media and the university. For anyone but a hardened German-hater, it is hard to finish this book without snorting in disgust at any attempt to portray Germany's re-education as a "necessary precondition" for a free society.

What might have happened without such a drastic, punitive intervention? It is highly doubtful that the postwar Germans would have placed rabid Nazis back in power. The country had had a parliamentary tradition and a large, prosperous bourgeoisie since the early nineteenth century, and the leaders of the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats, who took over after the occupation, all had ties to the pre-Nazi German state. To the extent that postwar Germany did not look like its present leftist version, it was only because it took about a generation before the work of the re-educators could bear its full fruit. In due course, their efforts did accomplish what Schrenck-Notzing claimed they would—turning the Germans into a masochistic, self-hating people who would lose any capacity for collective self-respect. Germany's present pampering of Muslim terrorists, its utter lack of what we in the U.S. until recently would have recognized as academic freedom, the compulsion felt by German leaders to denigrate all of German history before 1945, and the freedom with which "antifascist" mobs close down insufficiently leftist or anti-national lectures and discussions are all directly related to the process of German re-education under Allied control.

Exposure to Schrenck-Notzing's magnum opus was, for me, a defining moment in understanding the present age. By the time I wrote The Strange Death of Marxism in 2005, his image of postwar Germany had become my image of the post-Marxist Left. The brain-snatchers we had set loose on a hated former enemy had come back to subdue the entire Western world. The battle waged by American re-educators against "the surreptitious traces" of fascist ideology among the German Christian bourgeoisie had become the opening shots in the crusade for political correctness. Except for the detention camps and the beating of prisoners that were part of the occupation scene, the attempt to create a "prejudice-free" society by laundering brains has continued down to the present. Schrenck-Notzing revealed the model that therapeutic liberators would apply at home, once they had fi nished with Central Europeans. Significantly, their achievement in Germany was so great that it continues to gain momentum in Western Europe (and not only in Germany) with each passing generation.

The publication Unsere Agenda, which Schrenck-Notzing's institute published (on a shoestring) between 2004 and 2008, devoted considerable space to the American Old Right and especially to the paleoconservatives. One drew the sense from reading it that Schrenck-Notzing and his colleague Bergbauer felt an affinity for American critics of late modernity, an admiration that vastly exceeded the political and media significance of the groups they examined. At our meetings he spoke favorably about the young thinkers from ISI whom he had met in Europe and at a particular gathering of the Philadelphia Society. These were the Americans with whom he resonated and with whom he was hoping to establish a long-term relationship. It is therefore fitting that his accomplishments be noted in the pages of Modern Age. Unfortunately, it is by no means clear that the critical analysis he provided will have any effect in today's German society. The reasons are the ones that Schrenck-Notzing gave in his monumental work on German re-education. The postwar re-educators did their work too well to allow the Germans to become a normal nation again.

00:05 Publié dans Hommages, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : conservatisme, allemagne, caspar von schrenck notzing, hommage, criticon, révolution conservatrice, droite |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 16 avril 2012

The Heritage of Europe's 'Revolutionary Conservative Movement'

The Heritage of Europe's 'Revolutionary Conservative Movement'

A Conversation with Swiss Historian Armin Mohler (1994)

By Ian B. Warren

Introduction

Following the aftermath of the cataclysmic defeat of Germany and her Axis partners in the Second World War, exhausted Europe came under the hegemony of the victorious Allied powers — above all the United States and Soviet Russia. Understandably, the social-political systems of the vanquished regimes — and especially that of Hitler's Third Reich — were all but completely discredited, even in Germany.

Following the aftermath of the cataclysmic defeat of Germany and her Axis partners in the Second World War, exhausted Europe came under the hegemony of the victorious Allied powers — above all the United States and Soviet Russia. Understandably, the social-political systems of the vanquished regimes — and especially that of Hitler's Third Reich — were all but completely discredited, even in Germany.

This process also brought the discrediting of the conservative intellectual tradition that, to a certain extent, nourished and gave rise to National Socialism and Hitler's coming to power in 1933. In the intellectual climate that prevailed after 1945, conservative views were largely vilified and suppressed as "reactionary" or "fascist," and efforts to defend or revitalize Europe's venerable intellectual tradition of conservatism came up against formidable resistance.

Those who defied the prevailing "spirit of the times," maintaining that the valid "Right" traditions must be accorded their proper and important place in Europe's intellectual and political life, risked being accused of seeking to "rehabilitate" or "whitewash" Nazism. Germans have been especially easy targets of this charge, which is nearly impossible to disprove.

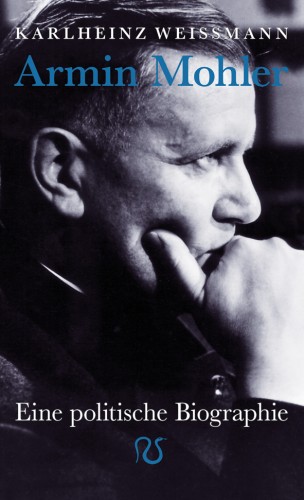

One of the most prominent writers in German-speaking Europe to attempt this largely thankless task has been Armin Mohler. As German historian Ernst Nolte has observed, this job has fortunately been easier for Mohler because he is a native of a country that remained neutral during the Second World War.

Born in Basel, Switzerland, in 1920, Mohler worked for four years as secretary of the influential German writer Ernst Jünger. He then lived in Paris for eight years, where he reported on developments in France for various German-language papers, including the influential Hamburg weekly Die Zeit.

In his prodigious writings, including a dozen books, Dr. Mohler has spoken to and for millions of Europeans who, in defiance of the prevailing political-intellectual order, have sought to understand, if not appreciate, the intellectual heritage of Europe's venerable "old right."

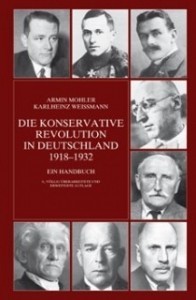

Mohler's reputation as the "dean" of conservative intellectuals and as a bridge between generations is based in large part on the impact of his detailed historical study, Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918–1932 ("The Conservative Revolution in Germany, 1918–1932"). Based on his doctoral dissertation at the University of Basel, this influential work was first published in 1950, with revised editions issued in 1972 and 1989.1

In this study, Mohler asserts that the German tradition of the Reich ("realm") in central Europe (Mitteleuropa) incorporates two important but contradictory concepts. One sees Mitteleuropa as a diverse and decentralized community of culturally and politically distinct nations and nationalities. A second, almost mythical view stresses the cultural and spiritual unity of the Reich and Mitteleuropa.

The main current of radical or revolutionary conservative thinking is expressed by such diverse figures as the Russian writer Feodor Dostoyevsky, Italian sociologist Vilfredo Pareto, American poet and social critic Ezra Pound, American sociologist Thorstein Veblen, and English novelist C. K. Chesterton. 2 This intellectual movement began at the close of the 19th century and flourished particularly during the 1920s and 1930s. Sometimes also called the "organic revolution," this movement sought the preservation of the historical legacy and heritage of western and central European culture, while at the same time maintaining the "greatest [cultural and national] variety within the smallest space."3 In Germany, the "Thule Society" played an important role in the 1920s in this European-wide phenomenon as a kind of salon of radical conservative intellectual thought. It stressed the idea of a völkisch (folkish or nationalist) pluralism, underscoring the unique origins and yet common roots of a European culture, setting it apart from other regions and geopolitical groupings around the globe. 4

In Mohler's view, the twelve-year Third Reich (1933–1945) was a temporary deviation from the traditional conservative thinking. At the same time, the conservative revolution was "a treasure trove from which National Socialism [drew] its ideological weapons." 5 Fascism in Italy and National Socialism in Germany were, in Mohler's judgment, examples of the "misapplication" of the key theoretical tenets of revolutionary conservative thought. While some key figures, such as one-time Hitler colleague Otto Strasser, chose to emigrate from Germany after 1933, those who decided to remain, according to Mohler, "hoped to permeate national socialism from within, or transform themselves into a second revolution." 6

Following the publication in 1950 of his work on the conservative revolution in Europe, Mohler explored in his writings such diverse subjects as Charles DeGaulle and the Fifth Republic in France, 7 and the Technocracy movement in the depression-era United States. 8 In 1964 Mohler was appointed Managing Director of the prestigious Carl-Friedrich von Siemens Foundation, a leading scholarly and research support institute in Germany. In 1967 he began a stint of several years teaching political science at the University of Innsbrück in Austria. That same year, Konrad Adenauer honored Mohler for his writing with the first "Adenauer Prize" ever bestowed.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Mohler was a frequent contributor to Criticon, a scholarly German journal whose editor, Caspar von Schrenk-Notzing, has been a close friend of the Swiss scholar and a major promoter of his work. In 1985, Dr. Mohler produced a collection of writings to commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Siemens Foundation. The volume contained contributions from the writings of Oswald Spengler, Carl Schmitt, Konrad Lorenz, Hellmut Diwald, H.J. Eysenck, and Julian Freund.

Mohler is a leading figure in the European "New Right," or "Nouvelle Droite." (For more on this, see Prof. Warren's interview with Alain de Benoist, another major figure in this social-intellectual movement, in The Journal of Historical Review, March–April 1994.)

Year after year, political leaders, educators and much of the mass media take care to remind Germans of their important "collective responsibility" to atone for their "burdensome" past. This seemingly never-ending campaign has become nearly a national obsession — manifest recently in the enormous publicity and soul-searching surrounding the Spielberg film "Schindler's List." In Mohler's view, all this has produced a kind of national neuroses in Germany.

Mohler has written extensively on the particularly German phenomenon known as "mastering the past" or "coming to grips with the past" ("Vergangenheitsbewältigung"). He tackled this highly emotion-laden topic in a book (appropriately entitled Vergangenheitsbewältigung), published in 1968, and later re-issued in a revised edition in 1980. 9 Two years later he turned to the subject of German identity.10

In 1989 Mohler again boldly took on the issue of Germany's difficulty in coming to terms with the legacy of the Third Reich in what is perhaps his most provocative book, Der Nasenring ("The Nose Ring").11 [A review by M. Weber of this work appears in this issue of the Journal.]

With the reunification of Germany in 1989, the collapse of the Soviet empire, the end of the Cold War US-USSR rivalry, and the withdrawal of American and Soviet Russian forces from Europe, has inevitably come an earnest reconsideration of the critical issues of German identity and Germany's the role in Europe. This has also brought a new consideration of precisely how Germans should deal with the troubling legacy of the Third Reich and the Second World War.

Changing social-political realities in Germany, Europe and the world have given new significance to the views developed and nurtured by Dr. Mohler and his circle of like-minded "revolutionary conservatives."

Interview

This writer was privileged to spend a day with Armin Mohler and his gracious wife at their home in Munich early in the summer of 1993. After having spoken earlier with historian Ernst Nolte, I was interested to compare his views with those of Mohler. In particular, I was curious to compare how each of these eminent figures in German intellectual life assessed the present and future climate of their nation, and of the continent within which it plays such a critical role.

This writer was privileged to spend a day with Armin Mohler and his gracious wife at their home in Munich early in the summer of 1993. After having spoken earlier with historian Ernst Nolte, I was interested to compare his views with those of Mohler. In particular, I was curious to compare how each of these eminent figures in German intellectual life assessed the present and future climate of their nation, and of the continent within which it plays such a critical role.

Although his movement is restricted due to a serious arthritic condition, Dr. Mohler proved to be witty, provocative and fascinating. (In addition to his other talents and interests, he is a very knowledgeable art specialist. His collection of reprints and books of Mexican, US-American and Russian art is one of the largest anywhere.)

During our conversation, Mohler provided both biting and incisive commentary on contemporary political trends in Europe (and particularly Germany), and on American influence. Throughout his remarks, he sprinkled witty, even caustic assessments of the German "political class," of politicians spanning the ideological spectrum, and of the several generational strands forming today's Germany. As he explained to this writer, Dr. Mohler felt free to offer views without any of the "politically correct" apologetics that have hampered most native German colleagues.

Q: What do you see as the state of the conservative political movement in Germany today?

M: Well, first let me explain my own special analysis. I believe there are three possibilities in politics, which I characterize as "mafia," "gulag," and "agon." Each has been a possible or viable political form in twentieth century history. Of course, between the choice of the "gulag" and the "mafia," people will choose the latter because it is more comfortable and less apparently dangerous, or so it seems.

But what of this third option, which is taken from the Greek term "agon" ("competition" or "contest"), and recalls the ancient Hellenic athletic and literary competitions? I believe it is possible to have a society that is free of the politics both of the mafia and of the Left, but bringing this about is quite complicated. It is a pity that today we appear only to have a choice between the mafia and the gulag. Liberalism in the 19th century context was a positive idea with a serious basis of thought. Today, however, liberalism has become just another name for the mafia. I do not believe that political liberalism is able to govern in the modern world. My ideal is most apparent today in the "tiger" states of Asia, such as Malaysia, Singapore, Korea and Taiwan, which have dynamic free market, liberal economies, but without liberal politics.

Q: When you speak of a "third option," are you referring to the anti-capitalist and anti-Communist "third way" or "third position" advocated by some political and intellectual groups in Europe today that reject the establishment elites of both the traditional left and right?

M: No. I do not see any significant movement of that kind. What small steps are being taken in this direction are denounced as "fascist" or in the "fascistic style." The role of the modern mass media has destroyed any possibility of such "third way" politics. This means, unfortunately, that we must exclude the "agon" option. We are left only with the "mafia" or the "gulag" options.

Q: Are you therefore saying that a true conservative revolution is not possible? Is there now in Germany anything that might be called an authentic conservative movement?

M: At first, just after the war, we did have a certain kind of conservatism. Essentially, it had two aims: first, to be the Number One enemy of Communism; and second, it must be allied with America. It also had its origins in two forms of conservatism. One was Burkian [after Edmund Burke], what I have called Gärtner-Konservatismus — "Gardener Conservatism" — that is, merely attending to the cultivation and restoration of society as a gardener would. The other is the "humility conservatism" of the Christian churches. These were the only kinds of conservatism allowed by the Americans. After all, they were the ones who handed out the chocolates, and western Germany wanted that. What the entire population did not want was Communism.

At last this began to change, particularly with the publication in 1969 of Moral und Hypermoral by Arnold Gehlen. 12 This book opened the way to a real Conservatism. Gehlen used the term "conservatism," which I do not like because it implies merely wanting to hold on to something from the past. Most of the time "conservatism" is used to refer to rather trivial and stupid things. In any event, a year after Gehlen's book was published our journal Criticon was started. The first issue was devoted to Gehlen and his ideas.

And then there was the "War Generation." I am not referring here to the "Old Nazis," but rather to a second generation that no longer believed in the early romantic notion of revolutionary National Socialism. By 1942, the "Old Nazis" were effectively all gone. In Berlin, by then, all of the government posts were in the hands of young technocrats: the "second generation" of National Socialists. They were not interested in the stories of the Party's struggle for power, or in the fight against Communism.

And this generation — members of which I met in 1942 in the government ministries in Berlin — were in their 30s. A good example of this type is Helmut Schmidt, who eventually became leader of the Social Democratic party, and then Chancellor. He is very typical of this generation that had conducted the war: in the later war years, they played a major role in the government agencies and in the [National Socialist] party organizations. They were very much a group of "survivors."

Q: So they were the first "new" class?

M: Yes. This first "new class" — most of whom came of age in the 1940s — accepted the ideology of the Western allies because they told themselves, and others: "We lost the war, now at least we must win the peace." I worked for 24 years at the Siemens corporation with people of this type. I tried to encourage them to fight against government regimentation. But they replied, "you can do that, you are Swiss. We, though, have to trust the system, to appreciate the possibilities of life within this economy and society."

They didn't have to develop a liberal or free market economy, of course, because Hitler was intelligent enough not to socialize or nationalize the economy. He had said, "I will socialize the hearts, but not the factory." And the members of this "new generation" felt that there was no time to dwell on being individualist: "We must work. We lost the war, at least we must win this struggle."

They are completely different from their sons and daughters! This next generation, which is now between 40 and 60, you could call them the "unemployed" generation: too young to serve in the army of Hitler and too old to serve in the army of Bonn. Well educated, they sought only to work in a liberal, industrial society, vacationing in Tuscany. They've wanted money for themselves, not accepting any social responsibilities. They wouldn't think of sacrificing their blood in wars decided by Americans or Russians. In their youth they were Maoists, but not seriously so; after all, they want to live comfortably. They didn't want to work hard like the Asians. Disdaining such a goal, they declared, "Our fathers and mothers had to work too much." They wanted an easier life, and they succeeded. The money was there, and the larger political questions were settled for them by the Americans. So these were the "volunteer helpers" — the "Hiwis" or Hilfswilligen — of the Americans.

The young socialists of this generation rejected the idea of national and social responsibility. It regarded the notion that men must work, and that one must help others, as a secondary and not very important idea of old people. These are the sons and the daughters of the people of my generation, too. This is largely a destroyed or wasted generation.

I admire the "war generation" very much because they had a sense of responsibility, and furthermore, they didn't lie. They did not mouth the trivial and hackneyed old political slogans of liberalism; they were too serious to do this. They knew in their hearts that this paradise of the Bundesrepublik [German federal republic] would not be viable.

But now we have a generation in power that is not capable of conducting serious politics. They are not willing to fight, when necessary, for principles. Typically, they think only about having good times in Italy or the Caribbean. As long as the generation between the ages of 40 and 60 remains in power, there will be bad times for Germany.

The generation that is coming into its own now is better because they are the sons and the daughters of the permissive society. They know that money is not everything, that money does not represent real security. And they have ideas. Let me give my description of this generation.

For 20 years people like me were on the sidelines and barely noticed. But for the past six or seven years, the young people have been coming to me! They want to meet and talk with the "Old Man," they prefer me to their fathers, whom they regard as too soft and lacking in principles. For more than a hundred years, the province of Saxony — located in the postwar era in the Communist "German Democratic Republic" — produced Germany's best workers. Since 1945, though, they have been lost. The situation is a little bit like Ireland. Just as, it is said, the best of the Irish emigrated to the United States, so did the best people in the GDR emigrate to western Germany. After 1945, the GDR lost three million people. With few exceptions, they were the most capable and ambitious. This did not include the painters of Saxony, who are far better than their western German counterparts. (Fine art is one of my special pleasures.) Moreover, many of the best who remained took positions in the Stasi [the secret police of the former GDR]. That's because the Stasi provided opportunities for those who didn't want to migrate to western Germany to do something professionally challenging. In a dictatorship, a rule to remember is that you must go to the center of power.

Recently, in an interview with the German paper Junge Freiheit, I said that trials of former Stasi officials are stupid, and that there should be a general amnesty for all former Stasi workers. You must build with the best and most talented people of the other side — the survivors of the old regime — and not with these stupid artists, police and ideologues.

Q: Are there any viable expressions of the "conservative revolution" in German politics today?

M: You know, I'm a friend of Franz Schönhuber [the leader of the Republikaner party], and I like him very much. We were friends when he was still a leftist. He has a typical Bavarian temperament, with its good and bad sides. And he says, "you know, it's too late for me. I should have begun ten years earlier." He is a good fellow, but I don't know if he is has the talents required of an effective opposition political leader. Furthermore, he has a major fault. Hitler had a remarkable gift for choosing capable men who could work diligently for him. Organization, speeches — whatever was needed, they could carry it out. In Schönhuber's case, however, he finds it virtually impossible to delegate anything. He does not know how to assess talent and find good staff people.

Thus, the Republikaner party exists almost by accident, and because there is so much protest sentiment in the country. Schönhuber's most outstanding talent is his ability to speak extemporaneously. His speeches are powerful, and he can generate a great deal of response. Yet, he simply doesn't know how to organize, and is always fearful of being deposed within his party. Another major weakness is his age: he is now 70.

Q: What do you think of Rolf Schlierer, the 40-year-old heir apparent of Schönhuber?

M: Yes, he's clever. He clearly understands something about politics, but he can't speak to the people, the constituents of this party. He is too intellectual in his approach and in his speeches. He often refers to Hegel, for example. In practical political terms, the time of theorists has gone. And he is seen to be a bit of a dandy. These are not the qualities required of the leader of a populist party.

Ironically, many of the new people active in local East German politics have gone over to the Republikaner because people in the former GDR tend to be more nationalistic than the West Germans.

Q: What about Europe's future and role of Germany?

M: I don't think that the two generations I have been describing are clever enough to be a match for the French and English, who play their game against Germany. While I like Kohl, and I credit him for bringing about German unification, what I think he wants most sincerely is Germany in Europe, not a German nation. His education has done its work with him. I fear that the Europe that is being constructed will be governed by the French, and that they will dominate the Germans. The English will side with the French, who are politically astute.

Q: That is the opposite of the perception in America, where much concern is expressed about German domination of Europe. And yet you think that the French and the English will predominate?

M: Thus far, they have not. Kohl hopes, of course, that he can keep power by being the best possible ally of America; but that is not enough.

Q: Do you think that the influence of America on German identity is still important, or is it diminishing?

M: Yes, it is still important, both directly, and indirectly through the process of "re-education," which has formed the Germans more than I had feared. Where have the special German qualities gone? The current generation in power wants to be, to borrow an English expression, "everybody's darling;" particularly to be the darling of America.

Those of the upcoming generation don't like their parents, whom they see as soft and lacking in dignity. In general, I think that younger Germans are not against Americans personally. They will be better off with Americans than with the English or French. In this I am not as anti-American as Alain de Benoist. The "American way of life" is now a part of us. And for this we have only ourselves to blame.

For my own part, I see a great affinity between Germany and America. When I was visiting a family in Chicago a few years ago, I felt right at home, even if it was a patrician family, and I am from the lower middle class. I felt something. For example, if I were to have an accident, I would prefer that it occur on the streets of Chicago rather than in Paris or London. I think that Americans would be more ready to help me than people in France or England.

During my travels in the United States, I encountered many taxi drivers, who were very friendly if they had an idea that I was from Germany. But when I would tell them that I am Swiss, they didn't respond in this positive way. In the case of Black taxi drivers, there is always the same scenario when they converse with Germans. They say, "you treated us as human beings when we were there."

Some would talk about those death camps on the Rhine for German prisoners run by Eisenhower, where American soldiers had orders not to give water or food to the Germans. 13 (You know, Eisenhower ordered that those who gave food or water to the Germans in those camps would be punished.) Blacks gave them water, though, and that had a great impression on them. To German soldiers they said: "We are in the same situation as you."

Q: You are saying that there is a camaraderie among victims?

M: Yes.

Q: How is it possible to throw off this domination, this cultural occupation, as it were?

M: I had the idea that we must have emigration — as the Irish have had — to make Germans more spontaneous. I have written on three different occasions about Ireland in Criticon.

It was not fair of me to judge Ireland during that first visit, because I did not know the country's history. Then I dug into the subject, and especially the 800-year struggle of the Irish against the English. I relied on the best study available, written by a German Jew, Moritz Julius Bonn. An archivist at the University of Dublin had given Bonn access to all the documents about the English colonization of Ireland.

In my second Criticon article I boosted Ireland as an example for the Germans of how to fight for their independence. I said that it was a war of 800 years against the English. At last they won. And the English genocide was a real genocide.

During my first visit to Ireland, I felt that there was something really different, compared to Germany. Last year, after two decades, I returned to Ireland. Writing about that trip, I concluded that I had been deceived earlier, because Ireland has changed. Europe has been a very bad influence. Every Irishman, when he saw that I was from Germany, asked me, "Do you vote for Maastricht?" [referring to the treaty of European unification]. When I replied that the German people are not allowed to vote on this matter, they seemed pleased. And to me, the Irish now seem very demoralized. Twenty years ago, when I arrived in a little Irish town in Castlebar, it was a quiet little town with one factory and some cars, some carts and horses. Now, all the streets were full of cars, one after the other. "Is there a convention in town," I asked. "No, no, it's normal." I then asked, "Are these cars paid for?" "Ah, no," was the answer I received.

Every person can have three days off a week, and then it's Dole Day on Tuesday. Their mountains are full of sheep. They don't need stables for them, because it's not necessary. The owners are paid a sum of money from the European Union for each sheep. Their entire heroic history is gone! It's like the cargo cult [in backwoods New Guinea]. For the Irish, the next generation will be a catastrophe. 14

Q: Returning to an earlier question: what does the future hold for German-American relations?

M: On one occasion when I was in America doing research on the Technocracy movement, I recall being the guest of honor at a conference table. At my side was a nationally prominent American scientist who was also a professor at a west coast university. Also with us was an internationally prominent Jew, a grey eminence in armaments who had an enormous influence. He was treated like a king by the president of the university. And at the other end of the table I sat next to this west coast professor, who told me that he didn't like the cosmopolitan flair of the East Coast. "You should come to western America," he said to me. "There you will not always hear stupid things about Germany." And he added that in his profession — he works in the forests and woods — are people who are friends of Germany. So I remember this fraternization between a visitor from Germany and someone from the American west coast.

Q: Are you suggesting that if it were not for the influence of certain powerful academic or political elites, there would be greater recognition of the compatibility of German and American values?

M: You see, this difficult relationship between Germans and Jews has had an enormous influence on public opinion in America. Jews would be stupid not to take advantage of this situation while they can, because I think Jewish influence in America is somewhat diminishing. Even with all the Holocaust museums and such, their position is becoming ever more difficult. This is partly due to the "multicultural" movement in the United States. Actually, the Germans and the Jews are a bit alike: when they are in power, they over-do it! New leaders in each group seem recognize that this is dangerous.

Dr. Mohler also spoke about the Historkerstreit ["Historians' dispute"], which he sees as a critical milestone on the road of enabling Germans to consider their own identity in a positive way. (For more on this, see Prof. Warren's interview with Dr. Ernst Nolte in the Journal, Jan.–Feb. 1994, and the review by M. Weber of Nolte's most recent book in the same issue.)

He expressed the view that many European leaders — particularly those in France and Britain — welcome an American President like Bill Clinton who does not seem expert at foreign policy matters.

With regard to developments in Germany, Mohler explained that he speaks as both an outsider and an insider, or as one who is "between stools" — that is, born and raised in Switzerland, but a resident of Germany for most of his adult life.

"With the Germans," he said, "you never know exactly what they will do the next day. You may become so involved in what is true at the moment that one thinks things will last for an eternity. People thought this about [Foreign Minister] Genscher." 15 In a closing comment, Dr. Mohler declared with wry humor: "In politics everything can change and the personalities of the moment may easily be forgotten."

Notes

- Mohler's most important work, Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918–1932, was first published in 1950 in Stuttgart by Friedrich Vorwerk Verlag. Second and third editions were published in Darmstadt. The revised, third edition was published in Darmstadt in 1989 in two volumes (715 pages), with a new supplement.

- See, for example: Ezra Pound, Impact: Essays on Ignorance and the Decline of American Civilization (Chicago: H. Regnery, 1960); Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899).

- Quote from Milan Kundera, "A Kidnapped West of Culture Bows Out," Granta, 11 (1984), p. 99. In his influential book Mitteleuropa, first published in 1915, Friedrich Naumann popularized the concept of a central European community of nations, dominated by Germany, that would be independent of Russian or British hegemony. Naumann, a liberal German politician and Lutheran theologian, sought to win working class support for a program combining Christian socialism and a strong central state.

- As one German intellectual puts it, "The renaissance of Mitteleuropa is first of all a protest against the division of the continent, against the hegemony of the Americans and the Russians, against the totalitarianism of the ideologies." Peter Bender, "Mitteleuropa — Mode, Modell oder Motiv?," Die Neue Gesellschaft/ Frankfurter Hefte, 34 (April 1987), p. 297.

- For a comprehensive discussion of the recent controversy over Mitteleuropa, See Hans-Georg Betz, "Mitteleuropa and Post-Modern European Identity," in The New German Critique, Spring/Summer 1990, Issue No. 50, pp. 173–192.

- Mohler, Die Konservative Revolution (third edition, Darmstadt, 1989), p. 13.

- Die Konservative Revolution (third edition), p. 6.

- Die fünfte Republik: Was steht hinter de Gaulle? (Munich: Piper, 1963).

- The movement known as Technocracy began in the United States and was especially active during the 1930s. It focused on technological innovation as the basis for social organization. Among other things, Technocracy held that major social-economic issues are too complicated to be understood and managed by politicians. Instead, society should be guided by trained specialists, especially engineers and scientists. While rejecting the Marxist theory of "class struggle,' it sought to create unity among workers, notably in the industrial heartland of the United States. Much of the popularity of Technocracy derived from widespread disgust with the obvious failure of the social-political order in the international economic crisis known as the Great Depression (approximately 1930–1940). See: Armin Mohler, "Howard Scott und die 'Technocracy': Zur Geschichte der technokratischen Bewegung, II," Standorte Im Zeitstrom (Athenaum Verlag, 1974).

- Vergangenheitsbewältigung, first edition: Seewald, 1968; second, revised edition: Krefeld: Sinus, 1968; third edition, Sinus, 1980. Mohler dedicated this book to Hellmut Diwald. See: "Hellmut Diwald, German Professor," The Journal of Historical Review, Nov.–Dec. 1993, pp. 16–17.

- Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing and Armin Mohler, Deutsche Identität. Krefeld: Sinus-Verlag, 1982. This book offers views of several leading figures in the movement to restore German national identity. See also von Schrenck-Notzing's book, Charakterwäsche: Die Politik der amerikanischen Umerziehung in Deutschland ("Character Laundering: The Politics of the American Re-education in Germany"). This book, first published in 1965, was reissued in 1993 in a 336-page edition.

- Armin Mohler, Der Nasenring: Im Dickicht der Vergangenheits bewältigung (Essen: Heitz & Höffkes, 1989). Revised and expanded edition published in 1991 by Verlag Langen Müller (Munich).

- Arnold Gehlen, Moral and Hypermoral. Frankfurt: Athenäum Verlag, 1969.

- See: James Bacque, Other Losses (Prima, 1991).

- Mohler recounted an anecdote about a German company that considered building a factory in Ireland. As the chief of the Irish branch of this company explained, "I can't run a factory with people about whom I can't be sure if they will arrive at 8:00 in the morning or 11:00 in the morning or if they arrive at all."

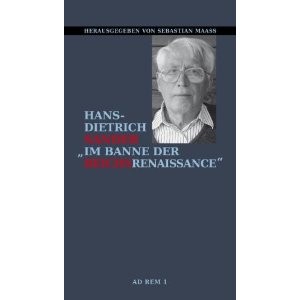

- The fall from power of Hans-Dietrich Genscher came suddenly and precipitously in the wake of the unification of the two German states in 1989. Mohler alludes here to suspicions that a number of West German Social Democratic party leaders may have been clandestine East Germany agents, whose national allegiance may have been mixed with some loyalty to international Marxism.

About the Author

Ian B. Warren is the pen name of Donald Warren, who for years was an associate professor of sociology at Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan, where he was also chairman of the university's department of sociology and anthropology. He received a doctorate in sociology from the University of Michigan. Among his writings were two books, The Radical Center: Middle Americans and the Politics of Alienation, published in 1976, and Radio Priest: Charles Coughlin, the Father of Hate Radio (1996). He died in May 1997, at the age of 61.

00:05 Publié dans Entretiens, Nouvelle Droite, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : armin mohler, allemagne, entretiens, révolution conservatrice, nouvelle droite |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 08 avril 2012

Spengler profeta dell'Eurasia

Andrea VIRGA:

Spengler profeta dell'Eurasia

Ex: andreavirga.blogspot.com/

Non ci si stancherà mai di raccomandare la lettura di Oswald Spengler (1880 – 1936), eclettico filosofo della storia tedesco e teorico del socialismo prussiano, le cui opere hanno riscosso successo e interesse negli ambiti più disparati, da Mussolini a Kissinger, dalla Germania di Weimar alla Russia contemporanea. Tra i vari motivi per cui risulta ancora oggi molto attuale, non possiamo non citare le sue ipotesi storiche riguardanti la Russia.

Non ci si stancherà mai di raccomandare la lettura di Oswald Spengler (1880 – 1936), eclettico filosofo della storia tedesco e teorico del socialismo prussiano, le cui opere hanno riscosso successo e interesse negli ambiti più disparati, da Mussolini a Kissinger, dalla Germania di Weimar alla Russia contemporanea. Tra i vari motivi per cui risulta ancora oggi molto attuale, non possiamo non citare le sue ipotesi storiche riguardanti la Russia. Nel 1918[1], mentre la guerra civile era ancora in corso, egli già prevedeva che la Russia avrebbe abbandonato nell’arco di pochi decenni il marxismo, per affermarsi come una nuova potenza imperiale eurasiatica – il che si è puntualmente avverato in questi ultimi anni. Noi vogliamo ora mettere a confronto il pensiero di Spengler con le attuali teorie eurasiatiste, che concepiscono lo spazio eurasiatico come di primaria importanza per la costruzione di un polo geopolitico alternativo a quello atlantico.

La sua tesi di fondo è che la Russia sia una realtà ben differente dalla “civilizzazione” occidentale, ma avente in sé tutte le premesse per la formazione di una nuova “civiltà”, la quale è ancora in una fase embrionale. Per analogia, la civiltà russa si trova perciò nella stessa fase di quella occidentale durante l’Alto Medioevo[2].

Questa civiltà era stata fino ad allora soggetta a forme ideologiche e culturali prettamente occidentali come il petrinismo e il leninismo, rispettivamente derivazioni di modelli occidentali come l’assolutismo e il marxismo, che le avevano impedito di esprimere il suo vero spirito. Tuttavia, era inevitabile, secondo il filosofo tedesco, che il bolscevismo sarebbe stato man mano superato e scartato dalla Russia, in favore di una forma politica più propriamente autoctona. Lo stesso bolscevismo russo, con Stalin, è andato assumendo caratteri decisamente nazionalisti e una sua politica di potenza a livello mondiale, interrotta dalla disintegrazione della potenza sovietica alla fine della Guerra Fredda, ma ripresa da Putin.

La “natura russa” (Russentum), «promessa di una Kultur [“civiltà”] a venire»[3], è modellata dal suo paesaggio natio, l’immensa piana eurasiatica che si estende oltre i confini delle civilizzazioni esistenti (Occidente, Islam, India, Cina), ed è infatti propria ai numerosi popoli, d’istinto nomade o seminomade, che vi vivono: slavi, iranici, uralici, altaici, ecc. Non dimentichiamo che, per l’occidentalista Spengler, «L’Europa vera finisce sulle rive della Vistola […] gli stessi Polacchi e gli Slavi dei Balcani sono “Asiatici”»[4].

Ancora più interessanti sono i rilievi che emergono dagli appunti postumi di Spengler dedicati alla protostoria[5]: nel Neolitico, delle tre grandi “civiltà” aurorali esistenti, che lui chiama Atlantis, Kush e Turan, quest’ultima occupa proprio la parte settentrionale dell’Eurasia, dalla Scandinavia alla Corea. L’uomo di Turan è un tipo eroico, in cui prevale il senso del tragico, dell’amor fati, della nostalgia e dall’irrequietezza data dai grandi spazi aperti. Queste caratteristiche si riscontrano per Spengler sia nel tipo prussiano sia in quello russo, il che contribuisce alla vicinanza tra questi due popoli. L’influenza di Turan si proietta inoltre dall’Europa al Medio Oriente, dalla Cina all’India, sulla scia della diffusione del carro da guerra indoeuropeo nel II millennio a.C[6], ponendo le basi per le civiltà successive.

Vediamo poi il significato politico delle teorie di Spengler. Robert Steuckers ipotizza che il comune substrato turanico potesse essere la base mitico-ideologica per un’alleanza politica tra il Reich tedesco, l’Unione Sovietica, la Cina nazionalista, e i nazionalisti indiani, in un’ottica anti-occidentale[7]. Viceversa, la critica coeva di Johann von Leers[8] accusava Spengler per la sua opera “Anni della decisione” (1933)[9] di voler formare un asse occidentalista e razzista con l’Inghilterra e gli Stati Uniti bianchi, di contro alle potenze di colore (America Latina, Africa, Asia, incluse Giappone, Italia e Russia). Non va però scordato che in scritti precedenti[10] aveva affermato chiaramente una maggiore affinità tra Prussia e Russia. La sua stessa interpretazione del bolscevismo russo come prodotto essenzialmente autoctono, in contrasto con quella antigiudaica delle destre europee anticomuniste, ha ispirato autori di tendenze nazionalbolsceviche come Arthur Moeller van den Bruck[11], Ernst Jünger, Ernst Niekisch, Erich Müller[12].

Risulta quindi evidente come Spengler, non adoperi il termine “Eurasia”, ma di fatto descriva quello stesso spazio (Raum) etnoculturale e geopolitico, identificandolo con una nascente civiltà russa, con caratteristiche sia asiatiche che centro-europee. La sua interpretazione della storia russa contemporanea coincide inoltre con l’interpretazione data dagli odierni eurasiatisti (Dugin, Baburin), ossia di una continuità nella politica internazionale tra zarismo, stalinismo e neo-eurasiatismo nell’affermazione della Russia come potenza eurasiatica.

[12] E. Müller, Nazionalbolscevismo, in Aa. Vv., Nazionalcomunismo, SEB, Milano 1996.

17:55 Publié dans Eurasisme, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : oswald spengler, eurasisme, eurasie, géopolitique, révolution conservatrice, allemagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 06 avril 2012

La Germania dionisiaca di Alfred Bäumler

La Germania dionisiaca di Alfred Bäumler